by Doug Becker

Even if you’re traveling at the speed limit down a long, straight stretch of road in the lower Great Plains, you can’t miss the beautiful and distinct Scissor-tailed Flycatchers on the lines and fences. Though at 65 mph, you may not see their striking black, gray, white, and salmon-pink coloration, but you can’t miss their conspicuously long “V” shaped tail. These fly catching birds don’t hide in the bush. In fact, whether you’re in town or the country, the Scissor-tailed Flycatchers are in the open, and can be easily seen and identified by any birder. In Texas, these beauties are simply known as the “Texas Bird of Paradise”.

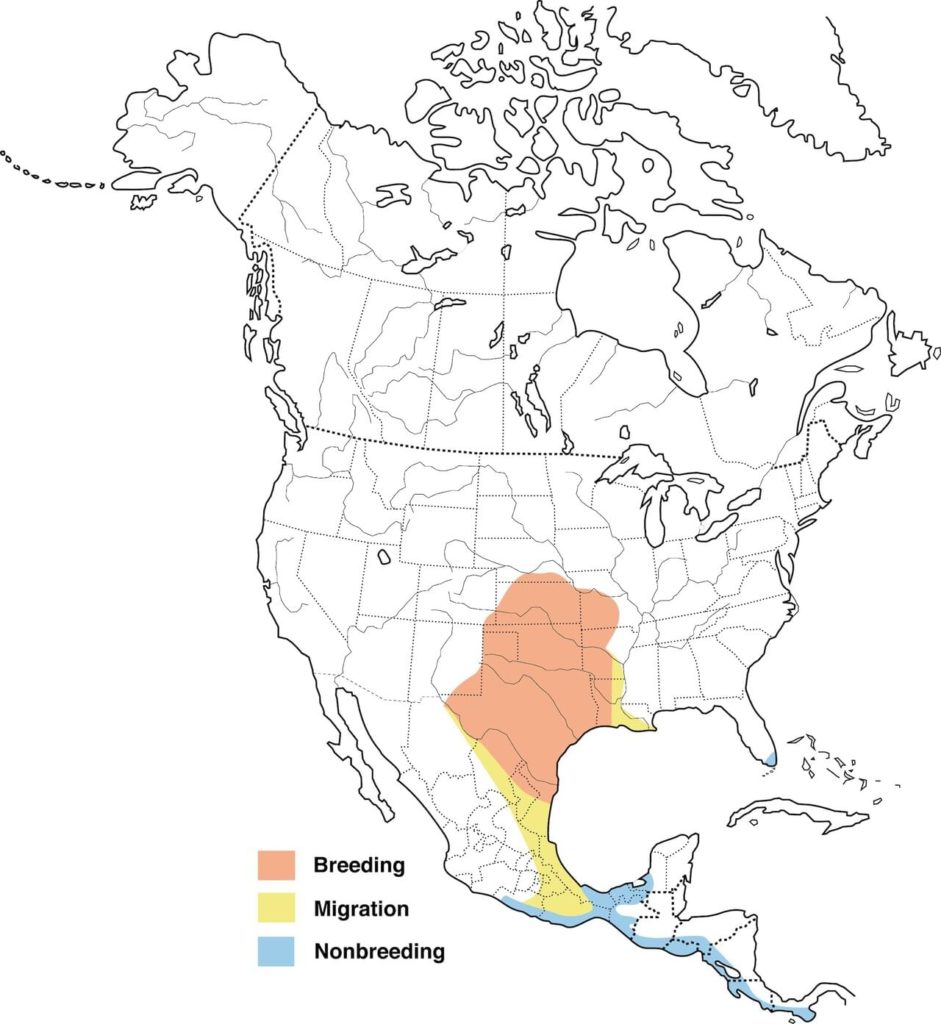

Their breeding territory is specifically in the Southern Plains of the U.S. This area goes from Kansas and Missouri, then south through all of Texas and Louisiana. Migration takes them into Mexico and Central America. Even though their breeding territory is very specific, in the Spring and Fall of the year they can be seen in most any part of our country, and even in British Columbia and Nova Scotia! These sightings are unusual, AND very exciting for birders outside of the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher’s normal range. Our first “positive” sighting was on the west coast of Florida. Debates have occurred over this. Some say we saw a Forked-tailed Flycatcher from Central and South America, but with the closeness of our sighting, our best birding binoculars and camera, I’m stickin’ with my Scissor-tailed Flycatcher ID! Isn’t birding fun?

The Scissor-tailed Flycatcher is in the King Bird family but is the only member of that family that has an unusually long, deep “V” shaped tail. The size of this bird is just smaller and leaner than a Robin, but with a length of up to 14.6 inches, they tend to look larger than they are. This extraordinary tail gives them their exceptional flying skills needed to catch flies in mid-air. Their feeding method is sometimes called “hawking” as they repeatedly zoom off from a perch to follow and consume a meal before returning to perch. Scissor-tailed Flycatchers eat only insects and a few berries. Grasshoppers, crickets, and beetles are favorites, but anything that can’t be eaten in flight gets taken back to the perch and gets beaten against a branch before it gets eaten. Backyard feeders will not attract these Flycatchers, but if you’re in their summer breeding area, you may be able to lure them into your yard by planting mulberry or hackberry bushes! Plus, they should be commonly found on telephone wires and fences. Slow-motion shows their beautiful and remarkable flight skills as their long tail enables them to hover and make 90 degree turns at will. Don’t forget your camera!

Nesting can get serious. The male and female will search their territory for just the right place. This can be in the open prairie, parks, croplands, gardens, pastures, or on the edge of a salt marsh. The nesting site is usually in an isolated tree or bush, sometimes even on a building, with nearby open space. The female builds the nest which can take a couple of days, or a couple of weeks. She first builds a rough frame that is 5-6 inches across, and is made of plant stems and flowers, oak catkins, wool, Spanish moss, peppergrass, tissue, paper, thread, and cotton. Ok, she’s got the frame done, now comes the inner cup that measures 3 inches across and 2 inches deep. This is made of closely knit cudweed flowers, string, cloth, cotton, and sometimes wet mud. Also used are caterpillar cocoons, sheep wool, Bermuda grass leaves, cedar bark, chicken feathers, seed silk, cigarette filters, paper, or carpet fuzz. And then … and finally … she lines the nest in tightly woven dried roots, thistle down, cotton fibers, and wooly cudweed leaves. Now all she has to do is lay 3-6 eggs 1-2 times per season. Incubation period lasts for 13-23 days, then nestling period for 14-17 days. Whew! This is one busy Momma! If it were me, it would take all summer to finally put my last cigarette filter in place before we all group up and fly off to Mexico!

Speaking of grouping up, that’s just what they do prior to their southern migration. These groups, or flocks, can number as many as a thousand birds. As the flock grows in this ritual, they will make a loud “bickering” sound among themselves. This, too, is a spectacle to see. No one can deny the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher with its extremely long tail and peachy-rose breast color showing from beneath slate-colored wings ranks among the most elegant and easily recognizable songbirds in North America. The fun is suddenly seeing a pair of Scissor-tailed Flycatchers outside of their territory and being shocked by their silhouette. Get those binocs out to see the rest of the story. Ain’t birding great? I’ll see ya out there!